铝是地壳中仅次于氧、硅元素的含量第三丰富的元素[1, 2]。由于酸性降雨以及人类日常活动涉及 (如用铝锅烹饪、化妆品和药品铝制包装等等),致使铝元素广泛存在于人类生活环境中[3-6]。此外,铝复合衍生产品广泛应用于食品添加剂和水处理方面[7-9]。然而,这种高浓度的铝含量对于植物、鱼类、藻类、细菌以及其他水生物种是有毒的[10-13]。铝在人体内的积累与肾脏损害也密切相关[14], 同时过量的铝摄入会使人类神经系统恶化,导致阿尔茨海默氏症、帕金森病等[15-18]。此外,铝在肠道内会影响人体对钙的吸收,导致骨软化;在血液中也会阻碍铁的吸收,导致缺铁性贫血[19-21]。世界卫生组织推荐人类每周膳食摄入铝的上限是7 mg/kg (体重)[22]。我国《食品添加剂使用标准GB 2760-2011》中规定,铝的残留量≤100 mg/kg。铝在人体内是慢慢蓄积的,其毒性缓慢且不易察觉,然而一旦发生代谢紊乱的毒性反应,则后果非常严重,所以必须引起人们的重视,在日常生活中要减少铝制品的使用,防止铝元素的过量吸收。因此, 加大对于铝离子的检测力度是十分必要的。

目前检测铝离子的方法很多,其中荧光分析法因具有快速响应与高灵敏度的特点,适合用于定性、定量检测铝离子,已成为研究的热点[23]。近年来,关于铝离子荧光探针的研究已有一些报道,但是绝大部分是“turn-on/off”型探针[24-25]。与turn-on型探针相比,由荧光光谱的迁移而产生的比率型探针可减少或消除如探针浓度、激发强度和检测效率等外界因素变化对测量荧光强度的影响[26-27],故本文以2-羟基-5-甲基苯甲醛、2-氨基苯硫醇、乌洛托品、烟酸酰肼为原料,采用分步法合成的方法得到具有不对称结构的Schiff碱化合物Ⅰ,并将其应用于对铝离子的荧光探针实验,结果表明该荧光探针通过比率型荧光变化对铝离子具有优良的选择性。

1 实验部分 1.1 试剂与仪器除非特别注明,所有试剂和溶剂从商业供应商处购买使用。所有实验中使用的均为去离子水。核磁共振1HNMR和13CNMR使用Bruker AM 400MHz核磁共振谱仪,质谱使用安捷伦6530质谱仪,吸收光谱采用α-1860紫外可见光谱仪。

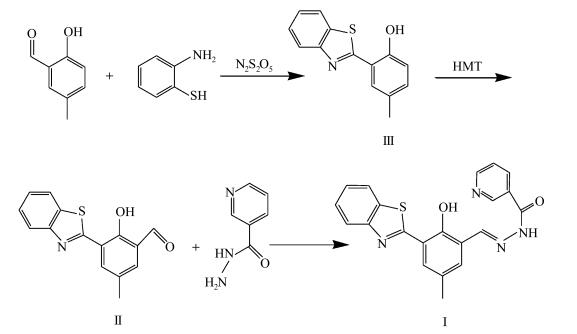

1.2 探针Ⅰ的合成过程探针Ⅰ的合成路线见图 1。

|

图 1 探针Ⅰ的合成路线 Fig.1 Synthetic route of probe Ⅰ |

在1000 mL单口烧瓶中,加入2-羟基-5-甲基苯甲醛 (5 g,36.75 mmol)、2-氨基苯硫醇 (4.6 g,36.75 mmol)、焦亚硫酸钠6 g,溶于100 mL的DMF溶液中,油浴加热至110 ℃回流反应4 h,冷却至室温后加水50 mL,有沉淀生成。过滤、水洗、干燥得淡粉色固体粉末8 g,产率90%。

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 12.24(s, 1H), 7.92(d, J=8.12 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J=7.96 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J=8.42 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.35 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.13(d, J= 8.32 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J=8.36 Hz, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H)。13CNMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 168.37, 154.75, 150.85, 132.72, 131.56, 127.66, 127.29, 125.61, 124.40, 121.09, 120.46, 116.62, 115.29, 19.45。

1.2.2 化合物Ⅱ的合成在250 mL单口烧瓶中,加入3 g化合物Ⅲ、9 g乌洛托品,溶解于50 mL的三氟乙酸中,油浴加热至100 ℃回流反应5 h,反应完成后加入20 mL浓度为4mol/L的盐酸,二氯甲烷萃取,抽滤溶剂得到黄色固体,通过硅胶柱层析法得到浅绿色固体5.58 g,产率约90%[28]。

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 12.99(s, 1H), 10.42(s, 1H, ), 7.98(d, J=8.12 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J= 7.96 Hz, 1H), 7.86(s, 1H), 7.64(s, 1H), 7.49(t, J= 7.62 Hz, 1H), 7.40(t, J=7.58 Hz, 1H), 2.34(s, 3H)。13CNMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 189.84, 165.91, 157.49, 150.35, 134.16, 132.08, 131.58, 127.91, 125.85, 124.81, 122.66, 121.32, 120.56, 117.60, 19.30。

1.2.3 化合物Ⅰ的合成在100 mL单口烧瓶中,加入269 mg化合物Ⅱ、160 mg烟酸酰肼,溶解于60 mL的无水乙醇中,油浴加热至80 ℃回流反应过夜,反应产生沉淀,过滤,反复使用无水乙醇冲洗得到淡黄色固体190 mg,产率50%(图 1)。

1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 13.22(s, 1H), 12.54(s, 1H, ), 8.82(t, J= 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.72 (s, 1H), 8.32 (d, J=8.08 Hz,1H), 8.19(d, J=7.4 Hz,2H), 8.10(d, J=8.04 Hz, 1H), 7.66(d, J=1.92 Hz, 1H), 7.63(m, 1H), 7.58(s, 1H), 7.50(t, J=4 Hz, 1H), 2.41(s, 3H)。13CNMR (100 MHz, DMSO) : 164.12、162.08、154.51、153.10、151.76、149.14、148.61、136.09、135.11、133.46、131.09、129.26、128.93、127.05、125.72、124.22、122.76、122.58、120.01、119.74、20.40。FAB-MS m/z=389.1036 (M+H)+, calcd for C21H16N4O2S=388.0994。

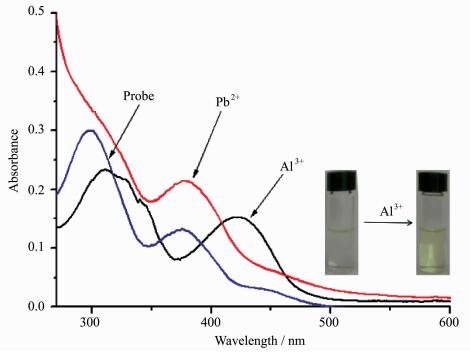

2 结果与讨论 2.1 探针Ⅰ对铝离子的紫外-可见吸收光谱响应如图 2所示,在紫外-可见吸收光谱中,10 μmol/L探针Ⅰ的DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液中,表现出2个主要吸收峰,分别位于300 nm和375 nm处。当加入铝离子后,在425 nm处出现一个新的吸收峰,这表示体系中逐渐生成了新的金属配合产物。由于425 nm处新的吸收峰的出现,肉眼可明显观察到溶液体系的颜色由无色逐渐变为淡黄色,从而实现了对铝离子选择性的直接观察。图 3为425 nm处各离子吸收强度的柱状图。

|

图 2 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS =1/99溶液, pH 7.4) 的选择性紫外光谱图 Fig.2 Selective UV-Vis spectra of probe Ⅰ (10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) |

|

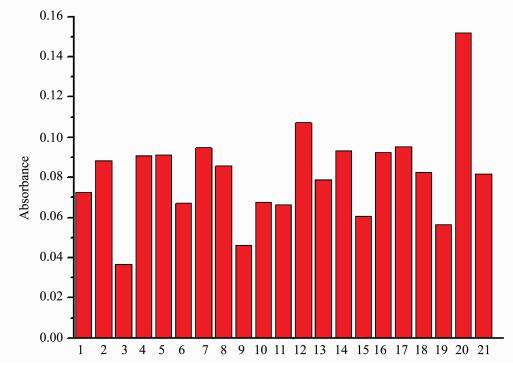

图 3 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液, pH 7.4) 对各金属离子紫外光谱响应图 1.Probe Ⅰ;2.Mn2+;3.Hg2+;4.Cd2+;5.Cr3+;6.Cs2+;7.Ag+;8.Co2+;9.Fe3+;10.K+;11.Mg2+;12.Cu2+;13.Zr4+;14.Na+;15.Ni2+;16.Ca2+;17.Zn2+;18.Li+;19.Eu3+;20.Al3+;21.Pb2+ Fig.3 UV-Vis spectra of Probe Ⅰ(10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) for different metal ions |

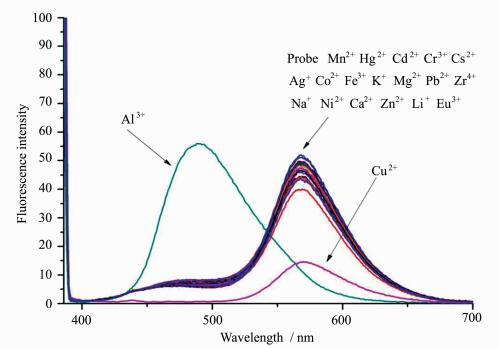

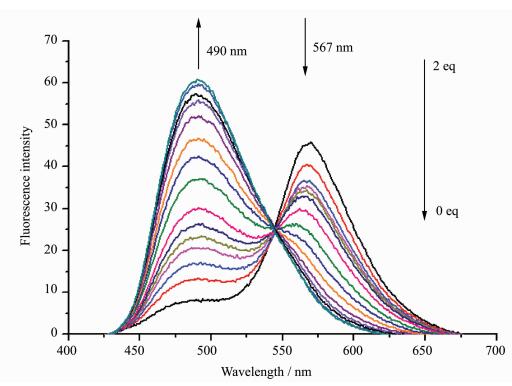

如图 4所示,探针Ⅰ的DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液为黄色荧光,在567 nm处表现出一个明显的发射。随着铝离子的加入,在490 nm处表现出明显的荧光增强。其最大发射波长,强度增大近60余倍。

|

图 4 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液, pH 7.4) 对不同离子荧光光谱图 Fig.4 Fluorescence spectra of Probe Ⅰ(10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) to different metal ions |

为了探究探针Ⅰ对铝离子以及其他金属离子的选择性相应,我们在3 mL的DMF/HEEPS (1/99) 溶液中,pH=7.4、探针Ⅰ浓度为10 μmol/L的测试条件下,依次加入30 μL 2 mmol/L的不同金属离子。如上图 2和图 4所示,探针对铝离子有较高的选择性,其中除Cu2+有少量荧光猝灭以外,探针对其他离子如Mn2+、Hg2+、Cd2+、Cr3+、Cs2+、Ag+、Co+、Fe3+、K+、Mg2+、Zr4+、Na+、Ni2+、Ca2+、Zn2+、Li+、Eu3+等均没有响应。实验结果表明探针Ⅰ是对铝离子在567 nm处荧光猝灭、490 nm处荧光增强的比率型探针。

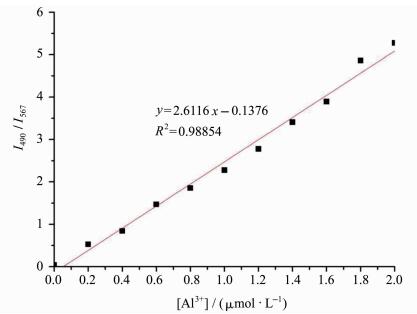

2.4 探针Ⅰ对铝离子的滴定曲线我们进一步探究不同浓度的铝离子对探针荧光光谱曲线的影响,在DMF/HEEPS=1/99的溶液中,pH=7.4、探针Ⅰ浓度为10 μmol/L的测试条件下,检测其探针随着铝离子量的变化所产生的荧光发射光谱的变化。如图 5所示,随着铝离子不断加入,探针Ⅰ在490 nm处的发射峰不断增强,567 nm处的发射峰不断减弱,最后当铝离子加到2当量时,发射峰的强度不再变化,在490 nm处其荧光增强了近60倍。此外,探针的荧光逐渐由红色变为绿色。通过黄色荧光与绿色荧光强度比 (I490/I567) 对铝离子的浓度作图,可以得到一条良好的线性关系曲线 (图 6)。根据下列公式计算检测限:

|

图 5 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液, pH 7.4) 在不同浓度Al3+下的荧光发射光谱 Fig.5 Fluorescence emission spectra of Probe Ⅰ(10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) in the presence of different concentrations of Al3+ |

|

图 6 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS=1/99溶液,pH 7.4) 的比率荧光强度 (I490/I567) 与Al3+之间的线性关系 Fig.6 Linear relationship between the fluorescence intensity of the Probe Ⅰ(10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) and Al3+ |

检测限=3σ/k

其中, σ为未添加检测物时探针分子荧光光谱变化的标准偏差,k为曲线斜率,计算得到该荧光探针对铝离子的检测限为0.5 μmol/L。

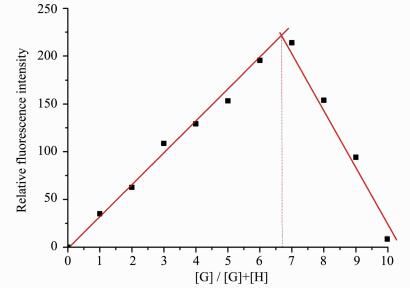

2.5 探针Ⅰ与铝离子结合比和结合常数的测定通过等摩尔连续变化法 (Job’s Plot) 测定探针Ⅰ与铝离子的结合比。固定二者与铝离子的总浓度为60 μmol/L,改变各自与铝离子的组成比例,所测定的荧光强度变化如图 7所示。可以看出,二者的荧光强度均在摩尔分数比为0.675时达到了最大值,表明了探针Ⅰ与铝离子的结合比均为2:1,即2个探针分子只与1个铝离子发生螯合作用,这与图 7所示的探针分子与铝离子反应的机理相符。

|

图 7 探针Ⅰ与Al3+的Job’s Plot曲线 Fig.7 Job's plot for Probe Ⅰwith Al3+ |

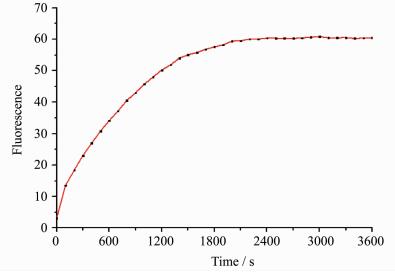

从图 8中可以看出,在加入10 μmol/L的铝离子后,探针Ⅰ在30 min内荧光强度增加到最大值,在30 ℃的水温下探针Ⅰ在1 min内荧光强度迅速增加到最大值。这一结果表明探针Ⅰ能够对铝离子快速响应。因此,该荧光探针将有望用于实时监测河水中的铝离子含量。

|

图 8 探针Ⅰ(10 μmol/L,DMF/HEEPS =1/99溶液,pH 7.4) 的时间关系曲线 Fig.8 The time curve of Probe Ⅰ(10 μmol/L, DMF/HEEPS=1/99, pH 7.4) |

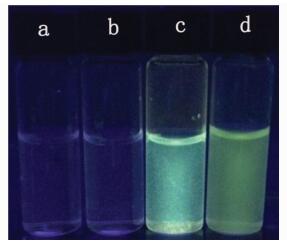

准备4个小玻璃瓶,在3个小玻璃瓶内各加入3 mL的普通河水,a不做任何处理,b中加入30 μL的2 mmol/L的铝离子,c中加入30 μL的2 mmol/L的铝离子和30 μL的1 mmol/L的探针Ⅰ,d中加入含有铝离子的工业废水 (铝离子含量约为0.6 mmol/L,且其中含有钠、钙、银等其他金属离子)。30 ℃下加热1 min后荧光灯照射结果如图 9所示:a和b未产生明显变化,c中有明显的绿色荧光产生,d中显示出的绿色荧光更加明显。

|

图 9 a.普通河水;b.普通河水+Al3+;c.普通河水+Al3++探针;d.工业废水 Fig.9 a.ordinary river water; b.ordinary river water+Al3+; c.ordinary river water+Al3++Probe Ⅰ; d.industrial waste water |

本文以苯并噻唑单醛为荧光基团修饰烟酸酰肼分子,设计合成了具有荧光增强性能的铝离子传感器Ⅰ。通过紫外-可见吸收光谱和荧光光谱研究了探针Ⅰ对铝离子的响应。通过铝离子与探针Ⅰ的结合比及质谱分析可知,2分子的荧光探针Ⅰ与1分子的铝相互结合时通过ICT (分子内电荷转移) 效应使得荧光光谱发生蓝移,即567 nm处的峰值不断下降,490 nm处的荧光逐渐增强。其检出限达到0.5 μmol/L,低于国家所规定的饮用水中铝金属的含量上限,同时,探针Ⅰ具有良好的选择性和抗干扰能力,可以应用于河水中铝离子含量的检测。综上所述,以苯并噻唑单醛作为荧光母体的铝离子探针具有良好的研究和应用前景。

| [1] | Delhaize E, Ryan P R. Aluminum toxicity and tolerance in plants[J]. Plant Physiology, 1995, 107(2): 315–321. DOI:10.1104/pp.107.2.315 |

| [2] | Godbold D L, Fritz E, Huttermann A. Aluminum toxicity and forest decline, Proc[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1988, 85: 3888–3892. DOI:10.1073/pnas.85.11.3888 |

| [3] | Zhang Y, Guo X f, Tian X j, Liu A d, Jia L h. Carboxamidoquinoline-coumarin derivative: a ratiometric fluorescent sensor for Cu (Ⅱ) in a dual fluorophore hybrid[J]. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2015, 26: 37–41. |

| [4] | Wang L, Li Y F, Li G P, Xie Z K, Ye B X. Electrochemical characters of hymecromone at the graphene modified electrode and its analytical application[J]. Analytical Methods, 2015, 7(7): 3000–3005. DOI:10.1039/C4AY03051F |

| [5] | Sarkar D, Pramanik A, Biswas S, Karmakar P, Mondal T K. Al3+ selective coumarin based reversible chemosensor: application in living cell imaging and as integrated molecular logic gate[J]. RSC Advances, 2014, 4(58): 30666–30672. DOI:10.1039/C4RA04318A |

| [6] | Maity D, Govindaraju T. Conformationally constrained (coumarin-triazolyl-bipyridyl) click fluoroionophore as a selective Al3+ sensor[J]. Inorganic Chemistry communication, 2010, 49(16): 7229–7231. DOI:10.1021/ic1009994 |

| [7] | Martin B R. The chemistry of aluminum as related to biology and medicine[J]. Clinical Chemistry, 1986, 32(10): 1797–1806. |

| [8] | Tennakone K, Wickramanayake S, Fernando C A N. Aluminium contamination from fluoride assisted dissolution of metallic aluminium[J]. Environment Pollution, 1988, 49(2): 133–143. DOI:10.1016/0269-7491(88)90245-X |

| [9] | Xin S G, Song L X, Zhao R G, Hu X F. Properties of alumi-nium oxide coating on aluminium alloy produced by micro-arc oxidation[J]. Surface and Coatings Technology, 2005, 199(2-3): 184–188. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2004.11.044 |

| [10] | Witters H E, VanPuymbroeck S, Stouthart A J H X, Bonga S E W. Physicochemical changes of aluminium in mixing zones:mortality and physiological disturbances in brown trout (Salmo trutta L)[J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 1996, 15(6): 986–996. DOI:10.1002/etc.v15:6 |

| [11] | Yang J L, Zhang L, Li Y Y, You J, Wu P, Zheng S J. Citrate transporters play a critical role in aluminium-stimulated citrate efflux in rice bean (Vigna umbellata) roots[J]. Annals of Botany, 2006, 97(4): 579–584. DOI:10.1093/aob/mcl005 |

| [12] | Kochian L V, Hoekenga O A, Pineros M A. How do crop plants tolerate acid soils mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency[J]. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2004, 55: 459–493. DOI:10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141655 |

| [13] | Yan F Y, Kong D P, Luo Y M, Ye Q H, Wang Y Y, Chen L. Carbon nanodots prepared for dopamine and Al3+ sen-sing, cellular imaging and logic gate operation[J]. Mate-rials Science and Engineering C, 2016, 68: 732–738. DOI:10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.123 |

| [14] | Sorenson J R J, Campbell I R, Tepper L B, Lingg R D. Aluminium in the environment and human health[J]. Environment Health Perspectives, 1974, 8: 3–95. DOI:10.1289/ehp.7483 |

| [15] | Savory J, Ghribi O, Forbes M S, Herman M M. Alumi-nium and neuronal cell injury: inter-relationships between neurofilamentous arrays and apoptosis[J]. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 2001, 87: 15–19. DOI:10.1016/S0162-0134(01)00309-9 |

| [16] | Walton J R. Aluminum in hippocampal neurons from humans with Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2006, 27: 385–394. DOI:10.1016/j.neuro.2005.11.007 |

| [17] | Croom J, Taylor L L. Neuropeptide. peptide Y Y and aluminum in Alzheimer's disease: is there an etiological relationship[J]. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 2001, 87: 51–56. DOI:10.1016/S0162-0134(01)00314-2 |

| [18] | Perlmutter J S, Tempel L W, Black K J, Parkinson D, Todd R D. MPTP induces dystonia and parkinsonism[J]. Neurology, 1997, 49: 1432–1438. DOI:10.1212/WNL.49.5.1432 |

| [19] | Baral M, Sahoo S K, Kanungo B K. Tripodal amine catechol ligands: a fascinating class of chelators for aluminium (Ⅲ)[J]. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 2008, 102: 1581–1588. DOI:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.02.006 |

| [20] | Yokel R A. The toxicology of aluminium in the Brain: a review[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2000, 21: 813–828. |

| [21] | Exley C, Swarbrick L, Gherardi R K, Authier F J. A role for the body burden of aluminium in vaccine-associated macrophagic myofasciitis and chronic fatigue syndrome[J]. Medical Hypotheses, 2009, 72: 135–139. DOI:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.09.040 |

| [22] | Berthon G. Aluminium speciation in relation to aluminium bioavailability, metabolism and toxicity[J]. Chemical Review, 2002, 228(2): 319–341. |

| [23] |

黄文君, 吴文辉. 荧光化学剂量计在汞离子检测中的应用[J]. 影像科学与光化学, 2011, 29(5): 321–335.

Huang W J, Wu W H. Fluorescent chemodosimeters for mercury (Ⅱ) ions detection[J]. Imaging Science and Photochemistry, 2011, 29(5): 321–335. DOI:10.7517/j.issn.1674-0475.2011.05.321 |

| [24] | Hossain S M, Singh K, Lakma A, Pradhan R N, Singh A K. A schiff base ligand of coumarin derivative as an ICT-based fluorescence chemosensor for Al3+[J]. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2017, 239: 1109–1117. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2016.08.093 |

| [25] | Panda U, Roy S, Mallick D, Layek A, Ray P P, Sinha C. Aggregation induced emission enhancement (AIEE) of fluorenyl appended Schiff base: a turn on fluorescent probe for Al3+ and its photovoltaic effect[J]. Journal of Luminescence, 2017, 181: 56–62. DOI:10.1016/j.jlumin.2016.07.008 |

| [26] | Li W L, Cai Y S, Li X, Hans A, Tian H, Zhu W H. Sterically hindered diarylethenes with a benzobis (thiadia-zole) bridge: photochemical and kinetic studies[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2015, 3(33): 8665–8674. DOI:10.1039/C5TC01796C |

| [27] | Cai Y S, Gao Y, Luo Q F, Li M Q, Zhang J J, Zhu W H. Ferrocene-grafted photochromic triads based on a sterically hindered ethene bridge: redox-switchable fluorescence and gated photochromism[J]. Advanced Optical Materials, 2016, 4(9): 1410–1416. DOI:10.1002/adom.201600229 |

| [28] | Chang C C, Wang F, Qiang J, Zhang Z J, Chen Y H, Zhang W, Wang Y, Chen X Q. Benzothiazole-based fluorescent sensor for hypochlorite detection and its application for biological imaging[J]. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2017, 243: 22–28. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2016.11.123 |